To ensure journalism reaches its intended audience, it is crucial that we journalists understand our users' needs: What is relevant to them? How would they like to be informed? And how can they communicate with us if they want to know more? This is more important in the digital age than it used to be since journalism is competing with countless other offers to capture people's attention.

It doesn't matter whether we are freelancers or content creators, whether we work for regional newspapers or major networks: At the Bonn Institute we see journalism as something that can be made by everyone, for everyone.

Constructive journalism is people-friendly journalism – journalism that expressly puts the common good and the interests of people at its core. In digital slang this is often described as "user-friendly," but we at the Bonn Institute are much fonder of "people-friendly."

Constructive journalism is a framework that provides us with criteria to better describe this focus and a clear orientation system – a "compass," as we like to call it – to further develop journalistic tools and our craft. We are working to this end with many partners and media organizations, in German-speaking countries and beyond.

Constructive journalism aims to give media users a future-oriented, fact-based, nuanced picture of reality. By researching solutions just as meticulously as problems, it counters a one-sided negative worldview and instead bolsters experiences of self-efficacy among media users by illustrating various potential courses of action. By consciously focusing on diversity and different perspectives, it reflects the world in all its complexity and counters oversimplification and polarization. And by redefining the role of journalists as moderators of a constructive public dialogue, it opens new possibilities for improved discourse in our society.

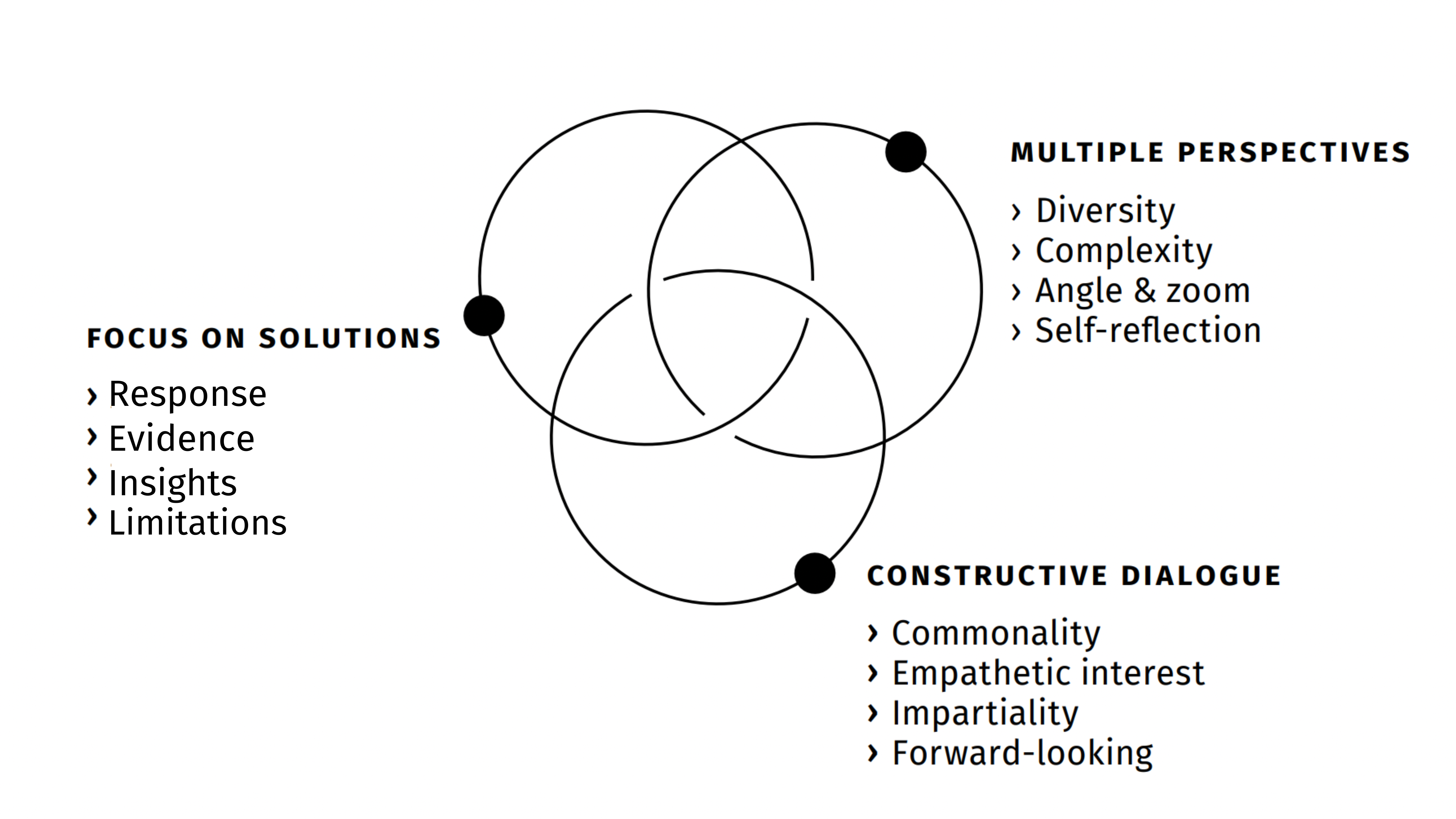

The Three Elements of Constructive Journalism

Focus on Solutions

Traditional journalism ends when a problem has been adequately identified or described. But constructive journalism goes a step further: It also reports on solutions to societal problems, thus expanding the scope of journalistic research. "Who is doing it better?" is one of the central research questions that solutions-oriented journalists pose.

Problem talks creates problems, solutions talks creates solutions

To ensure that reporting on possible solutions lives up to the demands of high-quality journalism, the Solutions Journalism Network has laid out four criteria that journalists should observe in their work. These characteristics can serve as a quality control checklist for researching and creating articles, and they aid solutions-oriented journalists in their efforts to avoid greenwashing, activism and PR.

1. Placing Possible Solutions Front and Center

Reporting focuses on attempts to solve a problem and examining how they work. Problems are also uncovered in solutions-oriented journalism, but reporting doesn't stop there. Instead, journalists research how they can be overcome. Solutions-oriented journalism shows how people can effectively deal with societal problems. A central question is, "Who is doing it better?" The solutions approach is not the light at the end of the tunnel, the last paragraph of an article loaded with problems; rather, it is the core of the story.

2. Evidence That Proves Effectiveness

The true effectiveness of an idea, not good intentions, is at the core of solutions journalism. This is why it investigates attempts to solve a problem that have already been implemented. When working on a strong solutions-oriented report, journalists look for evidence that proves an approach is effective. In addition, they can also examine studies and surveys that evaluate how successful various approaches have been. Effectiveness can also be qualitatively documented, for instance in discussions with the people that a given solution is intended to help or with independent experts.

3. Transferability of an Approach

A story's relevance lies in its transferability, since this shows why a particular (possible) solution is newsworthy. The aim is to share insights that others can learn from. Posing different questions is what makes solutions-oriented reporting unique. How exactly does this possible solution work? What do we need to know about it to be able to apply it elsewhere? To what extent does environment determine the success of a solution?

4. Limits and Hurdles

Only in the rarest of cases is a (possible) solution a one-size-fits-all fix. Journalists should not present ideas as miracle cures. Solutions journalism shows the limits of possible solutions just as critically as it investigates evidence. Success tends not to be a "yes or no" issue but an interplay of some factors that function and others that don't—or at least not yet. Something that works in one place may fail in another.

Multiple Perspectives

While solutions-oriented journalism primarily focuses on the journalistic craft, the idea of a wealth of perspectives additionally looks at systemic factors, be it in terms of personnel in a newsroom or department, or one's own blind spots and biases and how to better understand them: Is my perspective perhaps skewed by a habitual focus on the negative? Do I seek to confirm my own perspective while researching? Do we have enough diversity in our content-producing departments to truly reflect the diversity of our society?

Journalism that has a wealth of perspectives is relevant journalism because it has its sights focused on the information interests of many different people in our society.

1. Diversity

The breadth of perspectives in a department's reporting is intrinsically tied to the diversity of its staff. The Bonn Institute has identified a broad group of key diversity markers that include social, ethnic and geographical origins, religion, sexual identity and gender, and also family forms, education levels and place of residence.

Reporting that includes a broad range of perspectives has become an economic necessity for journalism catering to diverse target groups: "Only people who see their own life situations reflected in the media are willing to pay for it," writes the Neue deutsche Mediamacher*innen (New German Media Makers or NdM), a German NGO comprised of journalists with various backgrounds, on its website. At the same time, public media outlets in Germany are obliged to provide a basic public service aimed at delivering comprehensive information to all citizens. This can only happen if these outlets sufficiently depict the diversity of German society. In practice, this raises the question of whether every voice in society is allowed to speak.

2. Complexity

Reporting that includes diverse perspectives also counters the oversimplification of complex situations into two opinions, options or poles. Our world is not black and white, and only very few people have radical opinions. It is therefore the task of journalists to illustrate the shades of gray—or bright colors—if they want to avoid further polarizing our society.

How does that work in practice? Possibilities include visualization or working with data, or by integrating systemic thinking into our research: Who does this affect—beyond the "usual suspects"? If we successfully reduce binary thinking in content-producing departments, we also avoid presenting various perspectives as false equivalencies.

3. Angle and Zoom

Both zooming out to get a wider angle and zooming in for more detail can broaden our perspective and change our story. This can include adjusting the time frame in our research or choosing different geographic or societal foci.

Let's look at time frame: When reporting on Ukraine, for instance, one can select different starting points—namely Russia's invasion on February 24, 2022, or its illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014. Of course, one can go back further still, and each time one does, the story changes. Broader timelines often provide a more comprehensive picture of reality.

But one can also shift geographic focus: It is possible to report on a story on-site (e.g., the specific role arms deliveries played in recapturing a certain location) or in terms of international comparisons (e.g., which European countries have delivered what weapons).

The societal focus determines how a story is told. Here we can report from the perspective of an individual (micro), groups (meso) or entire countries (macro). Reporting that includes a wealth of perspectives means allowing for several different angles and degrees of zoom at once.

4. Self-reflection

How does my reporting affect users? How does it influence the way they see reality? What influences my own view of reality? These and other questions make up the fourth characteristic of a wealth of perspectives: self-reflection.

Psychology long ago recognized that our brains, despite their best efforts to understand the world, subconsciously default to experience-based thinking patterns and heuristics. Proven and usually unconscious shortcuts are supposed to save us from overexertion and provide us with orientation. But habitual ways of thinking can also lead to flawed conclusions and cognitive distortion.

We at the Bonn Institute have made it our task to build a bridge between journalism and psychology, since it is essential that journalists recognize their own cognitive distortions in order to avoid confirmation bias, in which the brain is especially inclined to accept information that fits our personal worldviews. Recognizing such cognitive distortions helps us report as objectively as possible—although we also acknowledge that absolute objectivity is unattainable.

Constructive Dialogue

Constructive dialogue is the third central element of constructive journalism, for journalists are not only needed as mediators of relevant information and different perspectives but also as moderators between various societal groups. This makes constructive dialogue an important tool for organizing human understanding: It creates spaces (including digital ones) where people can exchange ideas; it facilitates conversations between people of various backgrounds; and it encourages and moderates peaceful, future-oriented debate on relevant societal issues. All this makes progress possible and can significantly contribute to social cohesion, as well as strengthen democracy and avoid corrosive polarization.

When it comes to developing journalistic debate formats, such as for TV, constructive approaches can provide exactly what surveys say users most want: They can present the core of a problem in detail, convey information and provide orientation with respect to the future and possible solutions, all the while focusing on dialogue and mutual understanding.

Here, too, the Bonn Institute has mapped out four criteria that have been gleaned from insights in mediation research and related social and communications psychology strategies.

Every good conversation requires listening and accepting the basic premise that the other could be right.

Constructive dialogue can also be an important tool in creating a lasting and viable connection between journalists and the public. Key aspects of this include continuous and intense exchange about user needs, the ability to reach new target audiences and communication that is built on equality and mutual respect. Such constructive dialogue leads to community building and community management that benefit journalists and media users alike.

1. Similarities, Not Differences

Instead of statically referring to different positions, constructive dialogue looks at similarities and possible solutions. This sets it apart from the many media debates centered around confrontation and division. Discussion is furthered when we ask: What justified interests or needs are hidden behind various positions? What is important or acceptable to all sides? Such questions open new perspectives and, in best-case scenarios, can also reveal shared paths.

2. Empathic Interest

The willingness to put oneself in another's shoes and seriously examine their position is a basic prerequisite for good discussion. This also holds true in a journalistic context, such as in interviews, panel discussions or conversations with users. Those who want to understand their interlocutor must first listen to them. Active listening—and posing questions as necessary—shows appreciation and fosters understanding. Thus, every good conversation requires listening and accepting the basic premise "that the other could be right," as philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer once said.

3. Omnipartiality

As moderators of public discussion, journalists can help resolve problems, just like mediators do in conflicts between individuals or groups. What can journalists learn from them in this regard? The fundamental professional attitude of omnipartiality is one important example. The term expresses how mediators should be equally empathetic to all sides and appreciatively attentive to making sure that everyone's concerns and expectations are heard. This is especially important in the case of societal groups that chronically go unheard, because they receive less professional attention, for instance. However, a professional attitude of omnipartiality reaches its limits when interlocutors fail to abide by the established rules of democratic discourse.

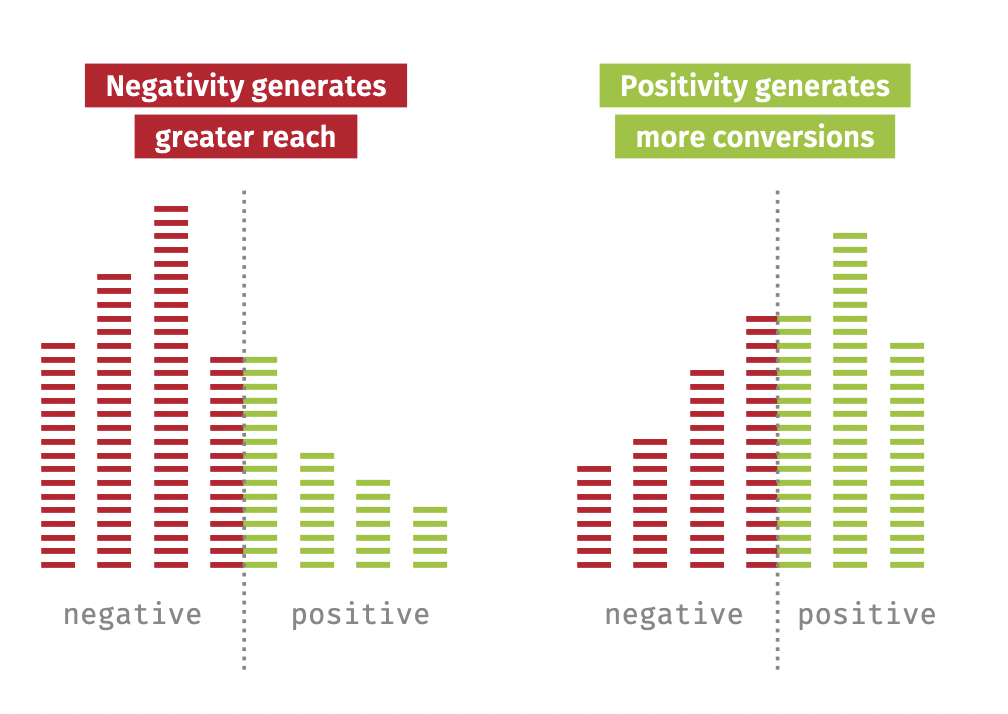

4. Forward-looking

Constructive dialogue has the future in mind. Instead of asking, "Why?" and "From where?" it asks, "To what end?" and "Where to?" Psychotherapist Steve de Shazer, a pioneer of solutions-oriented therapy, put it like this: "Problem talk creates problems, solution talk creates solutions." Journalism can also profit from this insight. Constructive journalism takes this into account through systematic questioning techniques that make it possible to look forward and show where there is potential.